Cyber threats are evolving rapidly. While attacks once primarily targeted technology, they now increasingly exploit human behavior. A misdirected document, a single click on a malicious link, or the reuse of a corporate password on an external service — and the entire infrastructure can be compromised.

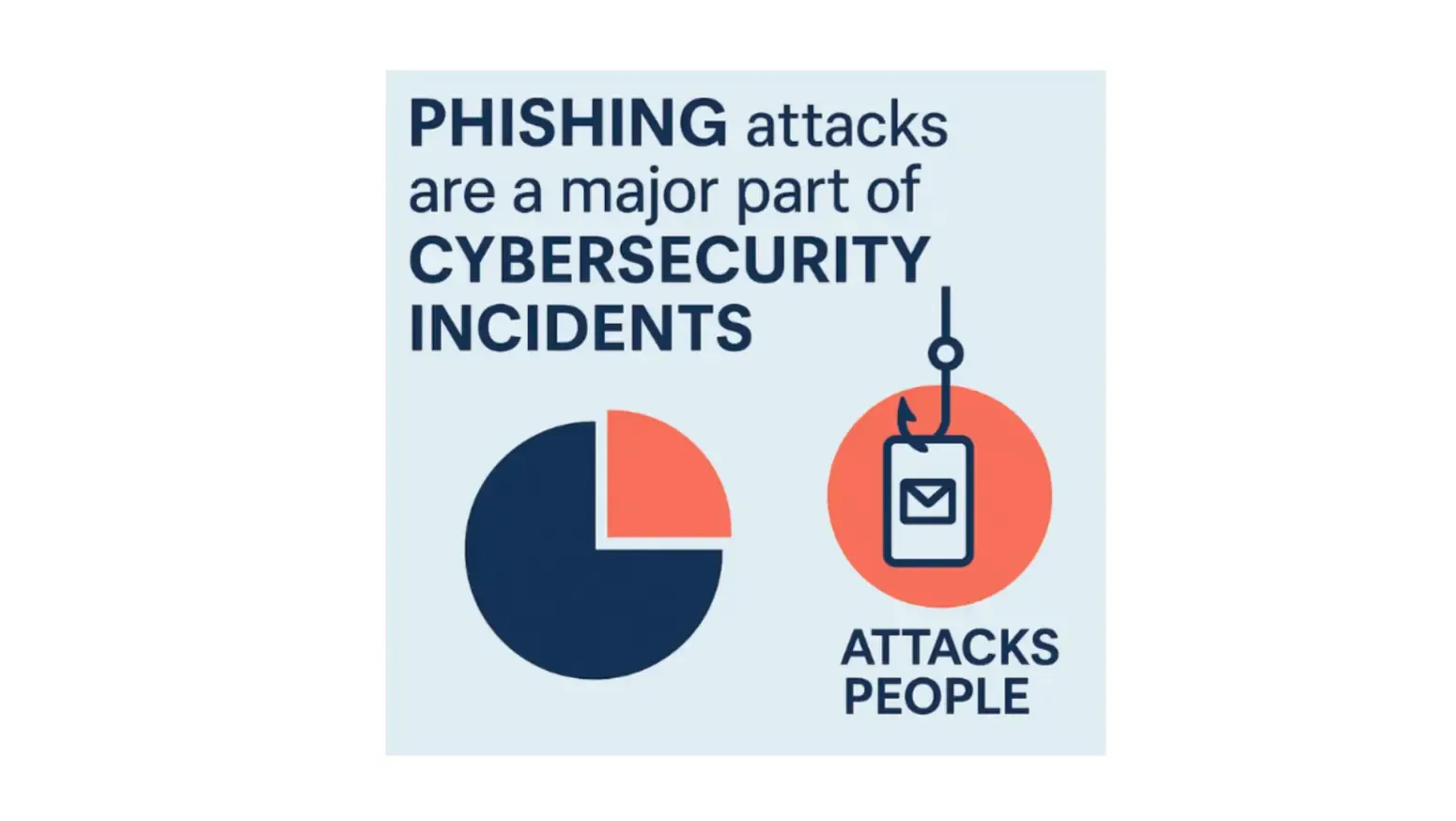

This isn’t just theory: the scale of the problem is consistently confirmed by data. According to the Verizon DBIR 2025, over 60% of cybersecurity incidents involve the human factor — including phishing, misconfigurations, weak passwords, and insufficient access control. This is not an exception, but a systemic risk that can’t be resolved with technology alone — only prevented by building a strong culture.

Not only in startups, but even in mature organizations, the use of technical tools does not compensate for the lack of behavioral resilience. Analysis confirms this: 88% of web-based attacks involved stolen credentials, and 22% of incidents began with compromised access.

This is not a matter of system configuration — it’s a matter of habits and everyday decisions.

Why Humans Are Still the Easiest Way In

Most modern technologies still rely heavily on people — for setup, maintenance, and daily use. Human involvement remains central to how IT systems function. In practice, attackers rarely choose the most complex way in. They go for the easiest — and more often than not, that path runs through a person.

Phishing emails, weak passwords, misconfigured settings, and accidental data exposure — these vulnerabilities aren’t caused by code flaws, but by habits and everyday decisions. That’s why in cybersecurity, the phrase goes: to break into a company, you don’t need to hack the system — you just need to hack the human behind it.

Phishing remains the most effective method of initial access — and it’s rapidly evolving. With AI, attackers now generate personalized messages, mimic voices and appearances, and even create deepfakes. These are no longer crude emails full of typos; they’re sophisticated, targeted, and hard to distinguish from real communication. That’s why employees become the first line of defense. Their awareness and response determine whether a message becomes a breach — or gets blocked in time.

One of the most striking cases of recent years is the $25 million deepfake phishing attack on the global engineering firm Arup. In early 2024, an employee in the Hong Kong office received a video call that appeared to come from the company’s CFO. The visual and voice were generated using AI-powered deepfake technology — realistic enough to convince the employee that the request was legitimate.

As a result, they authorized a large financial transfer — without realizing they were interacting with a synthetic video.

This wasn’t a technical breach. It was a behavioral breach, enabled by cutting-edge manipulation techniques and a lack of established internal skepticism.

This case is a textbook example of deepfake phishing: a new generation of social engineering attacks where AI-generated content replaces emails and links with video and voice impersonation.

How a Resilient Security Culture Is Built

It starts with leadership. Without a clear example set by founders or top executives, no security strategy will be taken seriously. When leadership visibly prioritizes security — by using multi-factor authentication, openly discussing risks during planning meetings, and asking questions about access configurations — the culture begins to form not through enforcement, but through imitation.

Then comes onboarding and education. It’s not enough to deliver a one-time lecture — secure practices must be embedded into the onboarding process: how access control works, how to report incidents, how to recognize real attack scenarios. Training should be ongoing and role-specific. A developer should understand secure coding principles, a designer — how to protect user data, a marketer — the risks of third-party platforms. In this context, security culture isn’t a universal checklist, but a set of resilient habits tailored to each function.

The turning point is integrating security into daily operations. When security review is part of every pull request, when risk assessment happens during feature planning, and when critical transactions require multi-person confirmation, security stops being a layer and becomes part of the process. In some companies developers are required to identify at least one potential security element in every pull request — even if it seems minor.

A Space Where It’s Safe to Ask and Safe to Be Wrong

Even with solid training and policies in place, a security culture cannot function without a foundation of trust. If employees don’t feel safe to ask questions or admit mistakes, the system stays silent until a crisis occurs. That’s why open communication channels matter — internal chats, formal reporting processes, and regular, low-pressure discussions about potential threats. In practice, when the focus shifts from punishment to dialogue and reflection, employees are more likely to flag suspicious activity — even if they’re unsure. This becomes the first layer of preventative defense.

And finally — reinforcement matters. Cultures built solely on restrictions tend to create passivity. In contrast, positive reinforcement — a thank-you for spotting something unusual, a quick mention during a team meeting, or a simple internal recognition — encourages engagement. Some teams even introduce lightweight gamification: who identified a phishing attempt first, who suggested a safer implementation, who improved access policy handling. In such environments, security becomes a part of team dynamics — not an external obligation.

Behavior Scales Better Than Software

Unlike tools that require deployment, maintenance, and regular updates, culture scales through behavior. New team members absorb it from more experienced colleagues, teams teach one another, and best practices spread horizontally. This is especially important for startups and fast-growing companies — culture builds resilience without the overhead that complex systems demand.

Cybersecurity in 2025 is no longer just about “tools against threats.” It’s about how a team makes decisions under pressure, how it responds to the unexpected, and how protective habits are embedded in daily work. In environments where employees see themselves as part of the defense — not as subjects of control — incidents happen less frequently and are resolved more quickly.

Because technology protects.

But people prevent.